It’s November, or as I’m calling it this year, Noir-vember, since I’ll be watching as many noir films as possible. What makes a story noir are the tropes. Yes, traditionally it means a movie with dark shadows that reflect the darkness that dwells in the human heart. But it’s come to mean a sort of crime story with morality and immorality in stark contrast.

Be sure that your sin will find you out.

With our daily darkness increasing and the inevitable crimes that will surround our electoral process, November is the perfect time to indulge in these sorts of stories. This niche genre may be able to offer some perspective and sooth our nerves as we head into this chaotic season and ground us. As much as noir delves into the gray areas of life, more often than not it holds up true truths. With as many lies as we’re subjected to in an election season, truth is a breathe of fresh air.

Even if it reeks of bourbon and cigarettes.

The hero of a noir is usually a bad man with a moral code. He has to be bad to survive effectively in an evil world, yet there are lines which he will not cross. Think of Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon, for example. He dallies with his partner’s wife and skirts the law. If he wanted to, he could hold the stuff the dreams are made of, and I don’t mean the Black Bird. But ultimately, he has to do what’s right and turn the killer over to the authorities, even though he’s come to love her.

We may not like him, but we respect him.

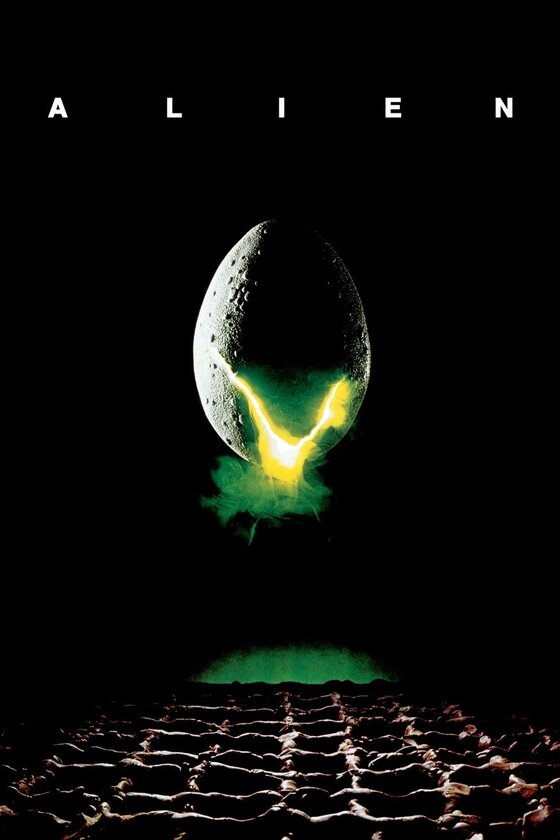

Lying is wrong. Adultery is wrong. Stealing is wrong. But murder is untenable, an affront not just to a single person but to the entire community. A human life is gone, and the lives of everyone who knew the victim will never be the same for the lack of his or her unique presence. It’s why Spade can’t allow the murderer to go unpunished, and why Chinatown is so horrific. It why, in so many noirs, even though we want the killer to get away with it, he cannot.

But back to Sam Spade and detectives like him.

They get results because they know how to operate in their evil worlds without becoming evil themselves. Make no mistake, it doesn’t make them good. They’re corrupt, too, just with different standards. Anti-heroes like this remind me of Donald Trump, in a way. He lies. He’s committed adultery. He’s probably stolen things. He’s corrupt. Nevertheless, I believe there are lines he won’t cross, and I fear that he has to be a little bad to effectively operate in the evil world of Washington politics.

I’m not voting for a pastor or head of my household. I’m voting for a president.

It’s entirely possible that by the time the dust settles he’ll lose again. Maybe Kamala Harris, the femme fatale, will take the reins of government. The thing about femme fatales is that, while attractive at first, they’re poison and are usually being manipulated by someone even worse. In order to survive, we’ll have to decide to resist despair and maintain our moral clarity, lest we become like Edward G. Robinson’s character in Scarlet Street.

Despair leads to desperation, and desperation leads to justification.

And here’s where one of the misused phrases of the Right applies. “Facts don’t care about your feelings.” That idea tends to get used as a bludgeon to “own the libs,” when really it’s just a fact. The fact is that actions have consequences, the heart is deceitful above all things, but God determines the outcome. Whatever evil we or they justify, because our hearts tell us it’s right—just this once—reality will inevitably trounce fantasy.

There will be consequences for evil actions.

Maybe we won’t see it here and now, living in Chinatown, but in Eternity all wrongs will be made right.

Sometimes we have to vote for the anti-hero, but that doesn’t mean that need to be one. At least, not all the time.