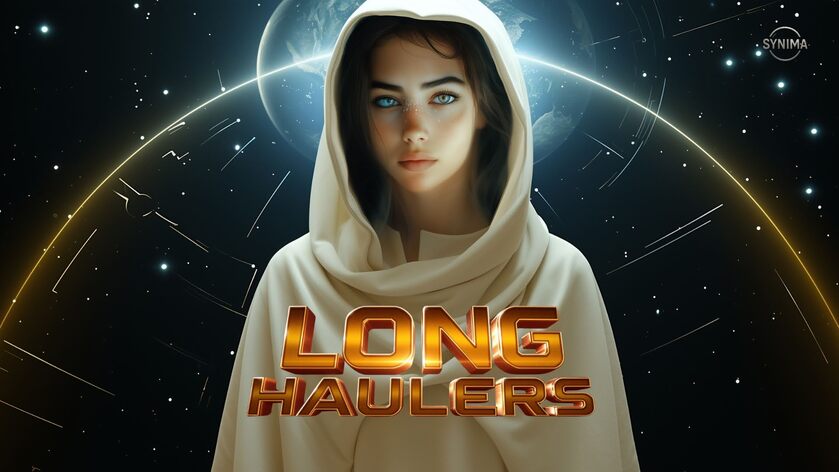

“How does the girl fit in this picture?”

“There’s always a girl in the picture. Haven’t you ever been to the movies?”

Before everything was meta, Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels was meta. It’s the story of director John L. Sullivan (Joel McCrea) who is tired of making goofy movies and wants to make O Brother, Where Art Thou? and “hold a mirror up to life.” Life in 1941 wasn’t all Mickey Mouse cartoons, after all. Sullivan feels that what’s really needed is “A true canvas of the suffering of humanity!” Of course, what does a hotshot Hollywood director know of suffering? Nothing. Everyone in his circle tells him that, and tries to tell him that audiences want to laugh, to escape their suffering.

So in his movie, Sturges does both.

The first act features a zany chase, with Sullivan in a kid’s homemade go-kart as they try to escape his entourage in a motorhome. People are bouncing off the walls, getting covered in food, popping through the roof, and a lady shows a lot of leg. It’s practically a cartoon. He eventually ends up in a boardinghouse run by an old lady who wants to seduce him, and ultimately ends up right back where he started in Hollywood. Undeterred, he goes back out into the world dressed as bum straight out of central casting.

Then he meets The Girl. Because there’s always a girl in the picture.

The Girl (Veronica Lake) doesn’t have any other name. Again, meta. Sullivan’s Travels is a movie within a movie, but none of the characters are in on it. We aren’t really supposed to notice either. The Girl, though younger, is more worldly wise than Sullivan. She moved to Hollywood to become a star, and now that she’s run out of money, is heading home. Lake, of course, is drop-dead gorgeous and delivers her lines with acerbic wit. Immediately taken with her and without giving away his act, Sullivan tries to convince her to stay until his ruse has ended.

It backfires and they end up getting arrested for stealing his own luxury sedan.

Once the cat is out of the bag, The Girl insists on going with him. This time, without his own press crew and doctor, to give Sullivan an authentic taste of life in the real world. The scenes play out in montage (one of several), surprising for such a wordsmith as Sturges, and yet the perfect choice. When Sullivan and The Girl reach their limit and call an end to the experiment, we might think that the movie is over and his arc completed. And we would be wrong.

Sullivan’s Travels is structured as a mirror image of itself.

I could write an entire essay on how it does this. Suffice to say, the madcap comedy of the first half reverses itself and becomes very dark in the second. Story elements are deliberately called back to, and not in ways so obvious that everyone will catch them on a first viewing. As clever as Sturges was he never felt the need to highlight that at the expense of the audience’s enjoyment. More than that, while he had a message that he wanted to make explicitly clear, he holds off until the very end.

“There’s a lot to be said for making people laugh. Did you know that that’s all some people have? It isn’t much, but it’s better than nothing in this cockeyed caravan.”

I used to be uncomfortable with this movie, wondering if the argument is for art for art’s sake. Now I realize that Sturges is arguing for anything but. O Brother, Where Art Thou? (Sullivan’s movie, not the Cohen Brothers’) was the self-indulgent, look how edgy and artsy and wise I am, art piece Sturges was advocating against. Sullivan’s Travels is art, not for its own sake, but to offer perspective to storytellers and joy to the masses.