A week ago the trailer dropped for a remake of The Crow and this week the Road House remake released. Both have reignited the discussion about what movies can be remade and which ones should be left alone. It’s practically a meme at this point that only bad movies with good concepts should get remakes, something which I’m not sure has ever happened. That could be about to change, as a new Red Sonja is in the works. The 1985 movie is as bad as you’ve heard, and a new version is finally exiting development hell.

Except it’s probably going to be just as bad in a different way.

We complain about remakes as if they're something new. What many people may not realize is that some of our favorite films are themselves remakes. Both The Wizard of Oz and The Ten Commandments, for example, are remakes of silent films. Many foreign films have been remade in English, with the location changed accordingly, and with good results.

It’s okay to remake a movie. Sometimes.

Generally, I'm of the opinion that the only time a remake is truly justified is when a new technology has been perfected. Silent movies remade as talkies? Sure. Black and white remade in color? Maybe, maybe not. When VR as an interactive, cinematic storytelling device is ready, I'll be ready for a remake of The Avengers.

No amount of rebooting will save the MCU until there’s new tech.

But Hollywood doesn't need a good reason to make a remake. Sometimes they just do it. Ironically, in the early days the studios often tasked the same director for the for project, or the director himself wanted to do it (Hitchock and DeMille being prime examples). Which I guess is better than George Lucas tinkering with Star Wars (Han shot first, btw).

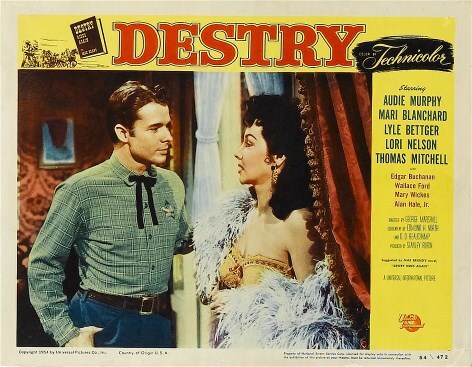

Such is the case with the movie I watched yesterday, Destry.

George Marshall had already done the Destry story in 1939 with James Stewart in Destry Rides Again, itself the second time Max Brand's novel had been adapted for the screen. So the next time you’re inclined to complain about the umpteenth Spider-Man movie, just remember this cowboy story you’ve never heard of got put to film three times.

Side note: neither the '39 nor the '54 movies bear any resemblance to the novel.

According to Wikipedia, the 1954 version is almost a shot-for-shot remake of Marshall's first pass. At least we rarely see that done anymore, though I wish The Crow would at least acknowledge of the color palate of the original (which I’m sure will look amazing in the 4k restoration). But I digress. I've seen the Stewart version, but it's been so long I don't remember it. What makes the ‘54 movie different is that one, it's in color, and two, it's got Audie Murphy.

Like Brandon Lee, we lost him too soon.

Both Stewart and Murphy are, of course, screen legends and real-life war heroes. But they bring very different personalities to the role. Stewart is known for his aw shucks, folksy awkwardness. Murphy, on the other hand, has boyish charm. Yet similarly, Stewart and Murphy were also very capable of portraying men with iron backbones.

Sometimes in the same movie. Usually in the same movie.

The story is pleasantly complex for an oater. When a corrupt mayor helps out a corrupt businessman in his land grab scheme by killing the sheriff and electing the town drunk to take his place, the drunk outwits them. He calls in the son of legendary lawman Destry to be his deputy. As is often the case in these older films, the hero doesn’t arrive on the scene until the stage is set.

But why is it always a land grab with these guys?

Young Destry already has a reputation for taming wild towns, but is very unlike his father: he refuses to carry a gun. However, he is wise beyond his years and soon has the local saloon girl rethinking her life choices (“I’ll bet there’s a beautiful face under all that paint. Maybe wipe it off sometime and take a look.”) even as he works to expose the previous sheriff's murder and establish law and order.

And have no doubt, when the time comes he can handle a gun.

I think this telling of the Destry story will stick with me longer than the Stewart version (or the novel, if we're being honest). Murphy is charming as always, and the supporting cast is full of familiar faces. The music and action are paced well, combining toward the end in a way I'm sure Tarantino loves.

Of all the Murphy movies I've watched recently, this could take the number one spot.

Maybe remakes don’t always have to surpass the original. Maybe they can even get away with being shot for shot redos with the same director. If the only change is the actor, and he’s right for the role, I’m willing to give the movie a chance and hope that it will be good. The problem is that most remakes today think the improvement they can make isn’t with technique or performance, but in pushing an agenda.

So that said, yes, I’ll be skipping The Crow and Red Sonja. But if someone wants to take a fourth stab at Destry, I’m interested.