It’s spooky season, and I’m watching monster movies. Last October I watched every episode of Kolchak: The Night Stalker (which if you haven’t seen it, you really should), and this year I’m catching up classic Universal Horror.

Last weekend I watched The Invisible Man (1933) and The Invisible Man Returns (1940). One of the things I appreciate most about these older films is that while they are short (the first one being all of 71 minutes), they are packed with story. They don’t feel short because they’re rich was detail, pathos, tragedy, humor, etc.

None of the recent films I’ve seen have that much depth, despite triple the runtime.

I’m not going to summarize the movies, because most people already have seen or have a sense of them. I do recommend watching the movies if you haven’t, though. Especially the first. It was Claude Raines debut role, and he doesn’t disappoint.

Also, the special effects need to be seen (or not seen) firsthand.

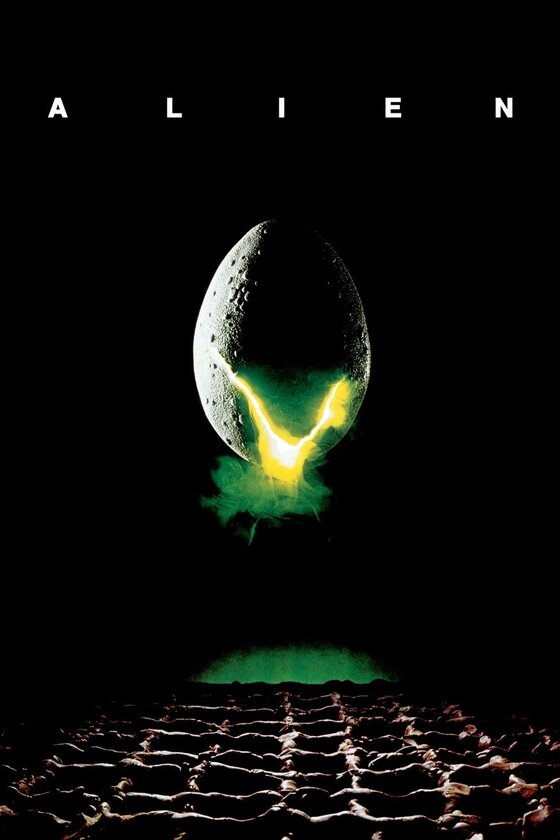

The Universal Monster Movies changed popular culture forever. They’ve defined how we think of Dracula (which is quite different from how he’s portrayed in the book), brought werewolves and living mummies into the mainstream, and become lasting icons even as the movie stars’ lights have faded.

Aside from the stunning visuals, why have the stories endured?

An entire book has probably been written about that, and I’m certainly not qualified, but let’s take a moment to consider The Invisible Man. It came out during a time of great scientific advancement, but when we as a culture still held to Christian values. There was room for both the natural and supernatural in the minds of the audience, and I can assume that there was still a bit of holy fear toward both.

People who thought they knew it all were rare, and to be distrusted, if not mocked.

Yes, it was a simpler time (I assume, since I wasn’t there), but what people did know was people. “We’re the real monster” is a trope now, but was it understood differently then? The danger of invisibility, of not having consequences for our actions, goes back to ancient myth. It corrupts.

Just ask Frodo.

When we compare the old horror movies with the new, we need to ask ourselves why they say man is the monster. And were the conclusions different then as opposed to now? There’s a different set of values in play, and once we learn how to work with those we’ll be a step closer to telling stories that last.

Here’s a hint.

There’s no room for self-righteousness in these stories. The heroes resist temptation to be the monster because they know that they aren’t perfect. It’s facing the monster within themselves that makes them heroic. There’s an element of humility on display that we’ve lost, both in our stories and therefore our culture.