Story never changes. At its core, every story dramatizes the hero’s eternal struggle between order and chaos — whether that conflict comes from nature, other men, God, or himself. But every so often, the medium for storytelling takes a huge leap forward. We’ll never know the epics that preceded that of Gilgamesh and the idea of putting fiction on clay tablets. Before that, stories were as effervescent and intangible as a whisper by a campfire. Just as fleeting, in some ways, were the plays of Shakespeare and his actors, and the Greeks before them.

Printing presses allowed a single author’s vision to spread, giving the world Don Quixote, Robinson Crusoe, Superman—and all the long-form literary fiction we take for granted today. Radio shows briefly took us back to “those thrilling days of yesteryear!” when motion pictures and TV were still luxuries. They were the evolution of the oral tradition, with the addition of dramatic music and sound effects, recorded for posterity. Today, most of us carry in our pockets devices that can hold thousands of books, or used to write one. Smartphones can show us movies, produce movies, and instantaneously share those movies.

Ironically, more than ever it seems like a good story is hard to find. The multi-billion dollar monolithic movie studios and publishers churn out hours of fresh content daily. No less prolific, given the sheer volume of them, are the independent artists, most working “real” jobs to pay the bills. They go largely unnoticed. Unless you’re directly involved, you may not realize how expensive it is to make something that looks and feels professional. There’s a reason Hollywood pours hundreds of millions of dollars into a single movie — they set the standard. There’s a reason indie films lean into esoteric artistry — no budget means no special effects, no recognizable locations, no union labor.

The Hollywood Bottleneck

The Hollywood machine has tar in its gears. Writing an amazing screenplay can take several weeks (if the legends are true). But getting it noticed by the right people can take decades — if it gets noticed. Then there’s the endless tinkering before production — if it’s produced. And should you ask anyone who’s been on set what making a movie is like, they’ll tell you it’s a lot of sitting around waiting. Lights and cameras have to be moved, makeup needs adjusted, endless minor details discussed. Actors are temperamental. Then there’s the editing, test screenings, and producers’ notes.

After going through so many filters, by the time a completed film arrives in theaters it’s homogenized and sterilized. The original idea that started it all is emulsified. And now, the industry is calcified. Worst of all, the average American finds his entertainment fortified (a nice word for polutifed) with an agenda antithetical to the reality he knows.

Galaxies in a Dewdrop

What if there was a way to remove budgetary shackles and create nearly at the speed of thought? What if instead of a series of writers, producers, studio heads, actors, directors, and focus groups, movies had a single vision? And what if that sort of power was given to an ordinary guy with an extraordinary imagination? That would be very dangerous to the cultural gatekeepers, and a good story might not be so hard to find.

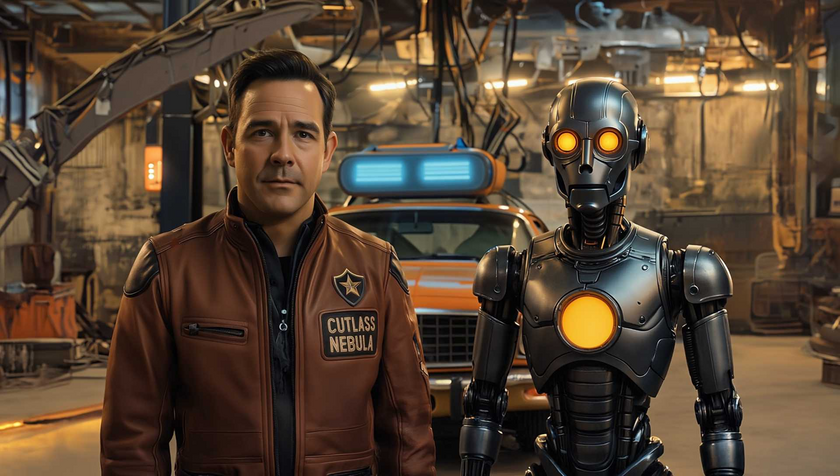

Michael McGruther is an ordinary guy with an extraordinary imagination, and thanks to developing AI technology, he’s creating the stuff of Hollywood’s nightmares and the everyday American’s dreams. His MacBook Pro is not only his writers’ room (where he meets with his writing partner, ChatGPT), but also his studio, backlot, editing suite, special effects house, and the honeywagon for his “actors.” With all these resources available, his is the singular vision behind Long Haulers.

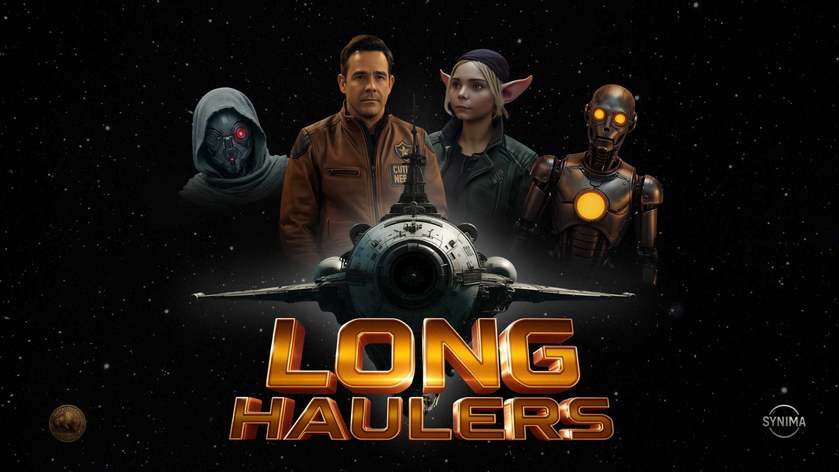

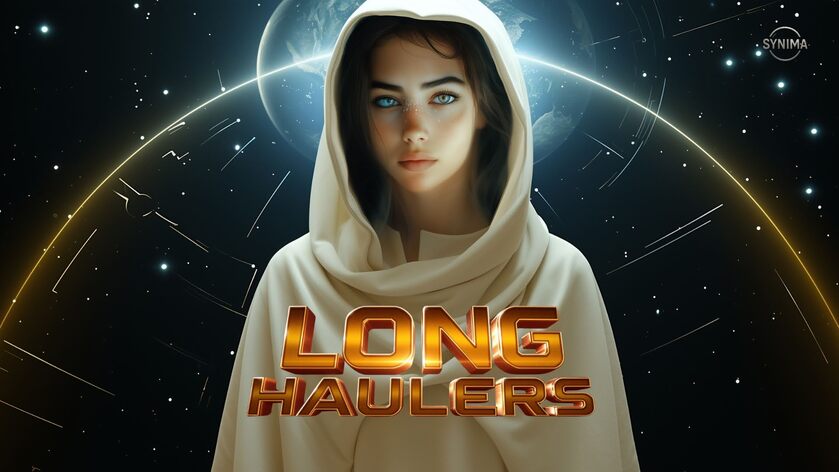

What started as an experiment with AI animation and an idea to make the opening credits to ‘80s-style sci-fi sitcom blossomed into a weekly web series. Long Haulers is the story of Knox Vega (who looks just like McGruther, so don’t come after him for stealing a celebrity’s likeness or try to borrow it for yourself), an interplanetary deliveryman on a mission. When all the jobs on Earth go automated, Knox has two choices: get drunk, or find a job with a purpose. Thankfully, he chooses the latter, accepting responsibility of the S.S. Grit and its cargo. With the help of the ship’s Virtual Integrated Research Assistant (VIRA, for short), who appears as a beautiful woman, he goes on a journey.

Each episode is written as a visual novel after conversing with ChatGPT about the plot. The AI isn’t creating the story, though, simply amplifying and clarifying McGruther’s ideas. If he needs market research to know what his audience likes, he can get that too, along with suggestions for incorporating those things into his story. While Disney is probably spending upwards of a million dollars (budgets are not known) per animated Star Wars episode, producing an episode of Long Haulers is probably closer to what you'd spend on dinner and a movie.

Codes: Computer and Moral

If your only experience with AI-created content is what you see on TikTok, it may seem trite and soulless. Admittedly, as we're still finding our way out of the uncanny valley, there’s still something a little “off” about these not-quite-human digital puppets. What sets Long Haulers apart, and sets all great stories apart, is intent. Unlike the viral TikTok reels, Long Haulers is more than a meme. Through the power of story, McGruther has something to say.

Long Haulers is indifferent to politics and preaching, and just puts Knox into situations where he must live out his beliefs. Ultimately, a character is a character, whether he’s described in words, played by Tom Cruise, or generated out of ones and zeros. Characters have moral codes, and in each episode Knox is driven by his own.

Trailblazing

Just as Knox is modeled on McGruther, more AI stars will be actors, who are working hand-in-hand with the storytellers. The pay may not be as spectacular, but the freedom and reach will be incomparable. Even now, the studios and talent agencies are scrambling to claim a stake in this new frontier. Can they sign an AI actor? Perhaps. But will real actors who can digitize themselves still want or need contracts and agents? It will depend on what they value: Freedom or Security.

Speaking of values, are Knox’s values (or for that matter, McGruther’s) our values? That’s something we’re invited to consider. McGruther shares what he believes through his art, and we can take it or leave it. So much coming out of Hollywood is a lecture from a soulless corporate collective. Worse yet, these lectures lack the conviction to look us in the eye, because the corporations are forever looking past the audience to the next bit of content they're going to sell. Long Haulers doesn’t tease us with the next thing. It is the thing. We’re invited to engage with the story to further refine what we feel and believe, just as McGruther interacts with ChatGPT to refine his narrative.

Looking Ahead

Will Knox Vega stand alongside Gilgamesh, Don Quixote, Macbeth, or Superman? Perhaps, perhaps not. Knox isn’t a complex character, and that’s the point. He was created organically, and his stories, despite the assistance of AI, don’t feel artificial. McGruther’s genuine passion for storytelling and belief that we can have a culture that heals rather than destroys comes through. Are there imperfections? Of course. Because McGruther, and every storyteller but God, is imperfect too.

Make no mistake, this is a landmark moment in storytelling. Without AI, we’d never be able to see the universe of Knox Vega as McGruther envisions it. A studio like Disney would never pour Star Wars money into such a project, and a novel, no matter how skillfully written, can only convey so much. In the early days of computer animation, Kerry Conran, director of Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, spent four years on a six minute short that eventually got Hollywood’s attention. If he’d had access then to the tools McGruther has now, he could have achieved that in an afternoon—and made his feature without leaving his Michigan home.

Hollywood’s golden age was filled with stories written and produced by war heroes, refugees, those who grew up poor in cities and on farms. Now it’s filled by those who grew up in a bubble devoid of real-life experience. The new advances in technology allow (not will allow, but do allow, right now) talented, everyday folk to tell stories with all the organic authenticity audiences have missed. Whether or not Hollywood survives is irrelevant. A new culture is here, and good story won’t be so hard to find.